Change

It’s been years, now, that we are supposed to live in a paperless world. Since the seventies, and the emergence of affordable and easy-to-use computers, the disappearance of notebooks, single sheets or post-it has been announced again and again. Yet, each day, we witness how wrong prophets were, who thought that screens and keyboards would simply replace paper and pens.

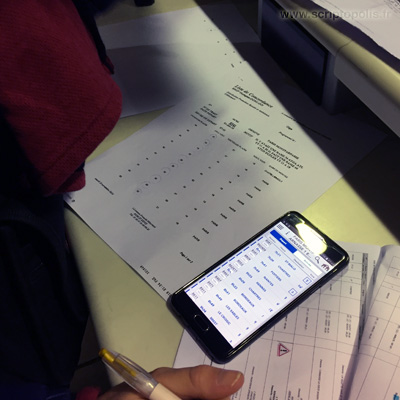

Take tickets, for instance. They are a nice example of a digitalized thing that did not totally eradicate paper. Admittedly, you can dowload your train ticket into your phone, and enjoy nice eletronic features such as real-time notifications and automated links to your calendar. But neither trains nor train seats are stable entities. Their identity and the numbers displaying it keep changing for reasons that remain largely unknown to most of us, and that have certainly a lot to do with linked databases and heterogeneous information systems. When these changes occur after electronic tickets have been generated and downloaded, there’s a chance that using a printer and a pile of paper sheets will be the best way to realign numbers, and through them, riders, their cars and their seats.

That is what happened to some of us recently. Just before boarding our train, we had to show our phone to a lady, who matched its screen to rows and columns in front of her, and gave us a new printed version of our ticket, with the right seat number on it. The day before, we were warmed by an e-mail that there was something wrong with the ticket we downloaded. An e-mail that some of us printed and took with them that morning, adding another layer of paper in the fragile coproduction of the trip, the train, its seats and passengers.