Choice

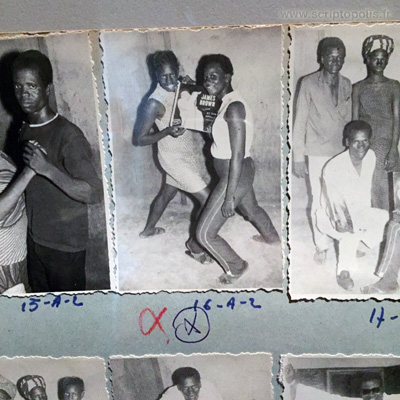

During the nineteen sixties and seventies, Malick Sidibé was a busy man. During the day, he spent his time in his studio portraying the people of Bamako. Some evenings, the younger ones, who were discovering the joys of rock and roll and twist, invited him to document their gatherings, where each dance step as well as each costume was an opportunity for a picture. When Malick returned from these epic parties, he would not go to bed until his films were developed. The next morning, everyone hurried to admire the pictures displayed in the front of his shop.

It is impossible to calculate the number of photos Sidibé took. Several thousands, at the very least. Over time, some of these images have seen their status changed. They began to travel far away from the streets of Bamako, while at the same time their author was morphing, at almost 60 year old, into a world-renowned artist, until he became one of the greatest names in contemporary photography.

The exhibition that runs at the Fondation Cartier until February 25th, gives a glimpse of the incredible strength of these pictures, which do much more than bear witness to an era and a city. In an enclosed space, you can discover some of Sidibé’s boards. Series can be appreciated as a whole. But there’s something else. Below or next to some of the vignettes a sign can be spotted, a small cross or a star. Because you have just seen a large official print, you understand this sign designates an image among the others that was destined to live another life, to stand out from the lot, to plunge into the worlds of art and to travel around the world, until it would find its way into galleries, museums and even dining rooms. Discovering these marks, we would like to be able to reconstruct the situations in which they were made. Why this picture and not this one? When and why was the choice made? For a book? An exhibition? A story in an international journal? It would take a full investigation of these signs to reveal these circumstances. Maybe this could even lead us to know who traced them. Indeed, however benign they may be, nothing tells us, except an old and disgraceful habit, that they were made by the artist himself, or even, in fact, that they are not the result of a collective operation.