Choreology

Paris, May 2018.

There are erudite notation systems to record human movement, like Meunier’s steno-choreography for classical ballet, and above all labanotation for modern dance and Benesh notation. The purpose of these so-called universal descriptions is, on the one hand, to transmit repertoire in the absence of the choreographer and, on the other hand, to facilitate the critical study of dance. Dance notations also supposedly allows works to be copyrighted. Anyway, it contributes to its patrimonialization.

Since the beginning of the 20th century, some choreographers have recorded their pieces by themselves, and national ballets have recruited choreologists for transcriptions. Yet academics and curators are the vast majority of the transcriptors. And if choreology has been part of the training given in Dancing Academies, video recordings have made it unnecessary for dancers.

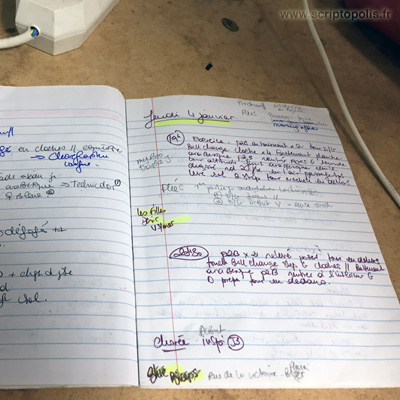

Yet writing still has ties with dance. Dorine Aguilar, like many others, keeps a notebook. No literal transcription, her body memory knows the exercises and variations. Twenty at the same time and for lessons it changes every month, she told. So to help the body, during her preparation, she notes the music (“Nocturne or Bjork” for the heating, “Les filles désir from Vendredi sur Mer” further on) and a few technical sequences that she does not yet know well (“two pas de bourrée turning forward, turn left, turn left, ball change, four cloches… “). Unlike movement notation systems turning to the future, her choreology is extremely fragile. Once her body no longer needs it to dance, ungrateful, it forgets the meaning of these inscriptions, which then also fall into disuse.