Distributed state throught

Émile Durkheim, the founder of scientific sociology in France, defines the state as a speculative power characteristic of modern societies. In this conception, the state should not be considered as a place (an assembly, an administration), nor as a social group (civil servants, politicians), and even less as a public policy (the education of children, the repression of crime), but as the maintenance of the intellection of the social world and the production, necessarily overflowing and continuous, of collective representations, which, in a communicative circuit, allow individuals to be subjected to common norms.

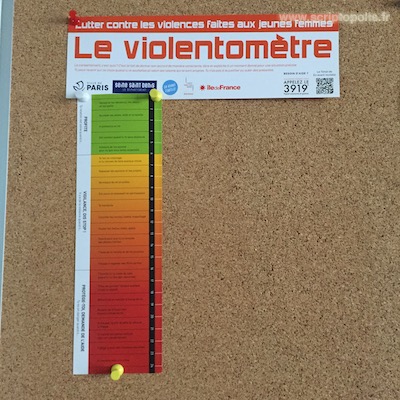

Although Durkheimism has been a fertile thought for the whole of the human and social sciences, few have claimed his conception of the State, deemed purely idealistic and insufficiently sociological. Yet there is something profoundly heuristic in the intuition that the state makes sense of the magma of our collective representations and holds the rules together. Consider, for example, the kind of object that Scriptopolis is fond of: the relationship violence meter for ‘young women’ that is displayed in the university corridors. Superimposed on a graduated ruler, the well-known chromatic spectrum of green to signify what is authorised, orange for borderline cases and red for what is forbidden, the object qualifies about twenty heterosexual couple situations and makes explicit the thresholds: “Enjoy, the relationship is safe when he respects your opinions and tastes”, or “Be vigilant, say stop when he searches your text messages, apps, emails”, and “Protect yourself, ask for help when he “goes crazy” when he doesn’t like something”. Beyond the government’s toll-free number and the logos of the institutions responsible for the policy of preventing violence against women in this area, the attempt to qualify situations, to define thresholds to make sense of pressing claims and to display this reflection in the public arena is perhaps what Durkheim drew our attention to. This invites us to consider that, far from a mentalist conception according to which the state would be housed in our minds, ‘the state in thought’ would be found in the ecology of those eminently material and distributed things that weave their way through our ordinary experience of the world.