Political phenomenology

When it doesn’t go unnoticed, our experience of the past in the present may provoke the beginning of a heuristic trouble for Scriptopolis: viewing photos, exploring family archives or administrative archives, rediscovering traces or events witnesses. Among the institutionalized experiences of the past, touring ruins, visiting a museum or reading historical plates prove particularly fertile ground for exploring reference to the past as a state activity.

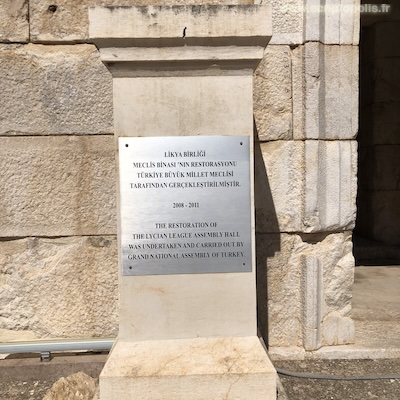

Just take the ruins of the ancient city of Patara. They stand out from the other Unesco World Heritage sites on Turkey’s Mediterranean coast for the visible, if not ostentatious, nature of their restoration. The stones have been cleaned, missing materials filled in, and glass panels and lighting placed on the ground so that the city’s political monuments can be seen from a distance. For tourists, the contrast is striking. As you approach the Bouleuterion, the narrow amphitheatre in which the city’s affairs were debated, you can’t miss this metal plaque affixed to a white marble stele. It reads, in Turkish and then in English, that between 2008 and 2011, Turkey’s Grand National Assembly funded the restoration of this edifice. So, at a time when the Turkish Republic was stepping up its legislative reforms and diplomatic initiatives in support of its bid to join the European Union, it was also carrying out, right in the stone, a work of interpretation summoning up an ancient civilization perceived as being the cradle of European democracy. In so doing, it stretched time beyond its Roman and Ottoman heritage.

Now, in 2024, for the tourists that we are, this sense of the democratic past through the selection of a certain historical heritage is actualized in a very different context. Since the 2017 constitutional reform, the President has had a right of veto over parliamentary activity, which has reduced the Grand Assembly to a recording chamber; in heritage matters, the once secularized building of Saint Sophia’s Basilica has been returned to Muslim worship in 2020; and the Republic no longer has any ambition of joining the European Union, as it now presents itself as the leader of Muslim countries in international negotiations. The phenomenologically-inspired reading of this stele thus reminds us that apparently abstract and stabilized political entities (the state, democracy or history) have a materiality, which can be deciphered in objects and can therefore always inaugurate new investigations, bearing witness to entangled temporalities.